by Michael Abraham

Take a star of anise and a pinch of lavender in either hand. Hold these to the chest and whisper out a little prayer. Splash clean water on the face. Brush the teeth. Fret over little details in the bedroom, whether the paintings are hung straight, whether the posters are in the right places. Shift the vase so it catches the morning sunlight. Light a candle. Pray again. Take three deep breaths and press your palms together, hard, in the way your therapist taught you. Give up on this and smoke a cigarette instead. Feel the smoke as it passes your teeth and scratches your throat. Turn your body to face the wind. Take in the wind—the dirty, city wind—and pretend it is lovely. Put in your headphones and play “Mama Said” by The Shirelles. Mama said there’d be days like this, there’d be days like this, my mama said.

***

The moment you realize you’re in pain may not be the moment in which you begin to hurt. You may hurt for days, months, years before you ever notice. But the moment you notice is essential. It is the defining moment of this season of your life. The moment you notice you’re in pain, you suddenly have agency; you suddenly have choices to make. Staring up at the ceiling of this little room in Brooklyn where I live now, I realize I have been hurting for years. The knowledge of this descends upon me like a great weight, and then, in the next moment, the weight recedes like a wave is pulled back out to sea. The weight recedes, leaving only the knowledge, like beach foam, something weightless but apparent, obvious, easy to spot. The knowledge glitters in the sun. Consider the glitter, the cruelty of it, the obviousness. Pain is so obvious except for when it is so routine that it disappears from notice. But, eventually, sooner or later, like the wave foam, pain will come forward in the mind; irrepressibly, it will make itself known.

What does one do with a pain one has felt for years without knowing its name? Knowing its name does not dispel it. Pain is not a demon that can be exorcised purely by knowledge of its name. Pain is something else entirely, not a foreign entity that creeps into the being from elsewhere, but a part of the being itself, something that rises up from the body and the mind and the soul as naturally as air rises from the lungs. Pain is the essential fact of human existence. Isn’t that what God said at the close of Eden, when he placed the flaming sword at the gates to punish Eve for choosing knowledge? You will hurt, my child. You will labor, and you will find yourself wretched. Those weren’t his exact words, and I don’t believe in God anyway. But if God gave us pain, who am I to refuse it?

***

I go on a little walk around my new neighborhood. Those first few walks around a new neighborhood are usually magical, but this walk feels like a desperate search for meaning. Twenty-seven, newly divorced, and suddenly awake to a pain whose name was long held in obscurity, I go walking. I find the deli that sells stolen cigarettes for ten dollars a pack (there’s always at least one), and I find the nearest iced coffee (a Dunkin’ Donuts connected to a gas station). I find the train lines and the nearest bars. Then, just a block from my house, I stumble on a tiny park.

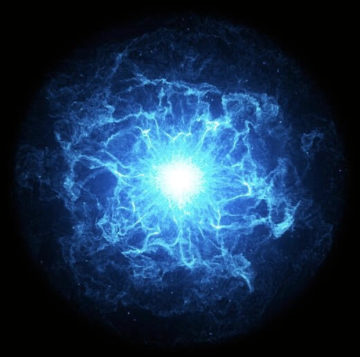

The park is made up of a handball court, a little turf field, and a concrete space lined with grassy patches and cherry blossom trees. It is beautiful in a common, city-planning type of way. But it strikes me. I sit down on one of two benches on either side of a concrete chess table and gaze around. On the handball court, two people in their early twenties are conducting some kind of photoshoot. To the left of them, on a bench, a woman is intently journaling. Across the park from her, on another bench, a man is staring off into space with a placid look on his face. I cannot explain why, but in this moment, surrounded by these specific people engaged in very different days, I feel my pain distinctly. It does not overwhelm me. It does not make me lament. I do not wish to be one of these other people in the park (certainly, they have their pains too). I simply feel it, tangibly, as though I could hold it in my hands and cradle it. It becomes a little, glowing ball, bright blue, and I marvel at it in this park, underneath the cherry blossom trees.

My little blue ball of pain. Or, rather, my little blue ball of meaning. For aren’t they the same, meaning and pain? Or, if not the same, aren’t they fellow travelers, going each where the other goes? Pain is roughshod but debonair. He goes about in rags, but he is alluring, sly, draws one in immediately with just one flick of his bright eyes. Meaning is pristine, beautiful, but stilted, haughty. She swishes her long, silk robes and dares anyone to make an approach. These two are the little devils at the core of every important juncture. Meaning and Pain: the mistress and master of crossroads. My little blue ball is full up with them. It is pure pain, pure meaning. And so I hold it in the park, and I ponder it: what does it mean? where does it hurt? I can sense their presence, meaning and pain, in my ball, but I do not know what they want from me. They are like a shrieking in the dark, almost sensible, but finally obscure.

***

I have been entirely too flowery, personifying and making images and worrying over the rhythm of sentences. What plainly happened is that I got my heart broken, not by the loss of love, but by love itself. I lost myself entirely in love, lost any sense I might have once had of who I was and what I wanted and how I wanted to be. I became desperate to hold it all together, my life, to keep what I thought was my life. And then, when it became very clear that the love which I mistook for life was untenable, I seriously considered trading in my life to keep the love perfect, for if I was not there, it would be as though the love were encased in glass, preserved forever. What I’m saying is that leaving was the least painful part of it. Indeed, I did not even feel the pain until after I’d left. So, now, I have an old pain, a pain born of love, a love which almost killed me, and I am to figure out what to do with it. I cannot wish it away, for it will not go away; my wishes are simply not that strong. I cannot share it with another, for it would be entirely unfair to do that. But I also cannot merely sit with it because I am fidgety and impatient, and it would never do for me to sit still and suffer.

***

While away the afternoon in books. Eat at least once. Or do not eat, but drink enough coffee not to notice. Try not to look too mournfully at the sunset. But gaze out the window all the same. Feel it as a part of you escapes out the window, wanders off into the wild world beyond the window and gets lost out there. Gather your sweater about you and go out into the windy evening to chase it. Wear a black cape to appear dramatic and interesting. Go to your friend’s concert. Stand toward the front, rock on your feet, toss your hair to the beat. Drink, but not too much. Or drink much too much and smoke the whole pack of cigarettes you bought on the way to the train. Just remember to smile, to smile at your friend, and your friend’s friends, and the strangers around you at the show. A smile shows you’re doing just fine. A smile is all that other people are looking for.

Come home and take a hot shower. Stand for a long time in the water, feeling it, really feeling it, across your drunken skin. Chat with your new roommate. Really listen when she tells you about her life, care what she has to say. This is the other thing people are looking for: care. Don’t fret that you don’t know how to care for yourself. That will come with time, with practice when you get up the gumption to finally practice it. Go back to your tiny room and make the most of it. Make the most of it.

***

It turns out I don’t know at all what to do with pain. It turns out I am no wiser than those who’ve gone before me, all of whom had this same question (everyone has this question). Give it time, my mother says. Sometimes, the old wisdom is the best. You see, I can’t just sit and suffer it; no, that won’t do. The trick is to live beside it, to subsist around the bright blue ball. It really is a trick; it does not come naturally.

But when I realize I have been living like this for years, bending around that little blue ball, I wonder to myself why I wrote this at all, what use it is to me or to anyone else. But, of course, where pain goes, meaning follows: it is necessary to try to make a meaning even if, finally, the only meaning there is to make is a shrug of the shoulders, an admission that there is nothing new to add to the question of what to do with pain. I write because I must, because pain demands meaning, because I have discovered the name of a pain that has made a home in me a long time, have learned its contours, its texture, its bright blue glow, and, having learned these, I must write them; I must write them or I will lose my mind in the discovery of the pain. What to do with an old pain newly dug up? Write it out. Write.