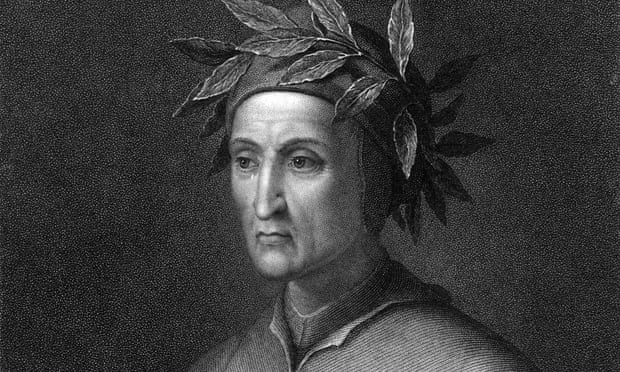

Seven centuries after the poet was found guilty in Florence, Sperello di Serego Alighieri has begun a campaign to clear his ancestor’s name

The reputation of Dante Alighieri needs little burnishing: his Divine Comedy, tracing the poet’s journey through Hell, Purgatory and Paradise, is widely regarded as one of the greatest works ever written. But more than 700 years after Dante was accused of corruption and condemned to be burned to death, his descendant is looking to clear his name.

Sperello di Serego Alighieri, an astrophysicist, and the law professor Alessandro Traversi are working to see if Dante’s 1302 sentencing for corruption in political office can be reversed.The Guardian view on Dante: heavenly wisdom for our troubled timesRead more

In the 14th century, Florence was divided between the Black and the White factions, formed after infighting among the Guelphs. Dante, a member of the White party, was accused of corruption when the Blacks took control of the city in 1301. His fine was 5,000 florins and two years’ banishment, with a permanent ban from public office. When he failed to appear in court in March 1302, he was condemned to death in absentia.

“They were political trials and the penalties of exile and death inflicted on Dante, my dear ancestor, are unjust and have never been cancelled as happened with Galileo Galilei,” Alighieri told Corriere Della Sera. “And therefore, if the laws allow it, we will ask for a revision.”

According to the Italian newspaper, any final judgment can be subject to revision if there is new evidence showing the offender’s innocence. There is no time limit to the request, which can be proposed by an heir of the convict.

“There were two sentences inflicted on Dante. The first was exile, the second was death and it will be interesting to understand whether in the light of the Florentine statutes of the time and the current legal principles the two judgments could be subject to revision,” said Traversi.

The plans to clear Dante’s name will begin with a conference in May, with participants including historians, linguists, lawyers – and Antoine de Gabrielli, the descendant of Cante de Gabrielli da Gubbio, the Florentine official who convicted Dante. They will be investigating if Dante’s sentences were just, said Traversi, or “the poisoned fruit of politics that used justice to attack an opponent”.

Not everyone is convinced of the need for rehabilitation. Writing in the same paper, journalist Aldo Cazzullo said that Dante “is the one who invented the word ‘belpaese’ [beautiful country]”. “What could a late acquittal add, however necessary?” he asked.