by Tim Sommers

How do we know that the external world exists in anything like the form we think it has? Assuming that we think, therefore we are, and that it’s hard to doubt the existence of our own immediate sensations and sense perceptions, can we prove that our senses give us reasonably reliable access to what the world is really like?

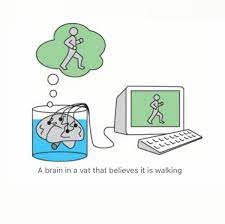

David (“The Hard Problem (of Consciousness)”) Chalmers, in his new book “Reality+”, doesn’t want us to think of these as skeptical scenarios at all. Being a brain in a vat, he says, can be just as good as being a brain in a head. Most of what you believe that you know about, say, where you work, what time the bus comes, or how much is in your checking account is still true, relative to your envattedness, according to Chalmers.

It seems tenuous to me to claim that “most” of your beliefs could be true in such a scenario.

But this isn’t the argument I want to have. I don’t want to examine these scenarios one at a time. I think the only scenario we need to look at to understand Chalmers’ central argument is the simulation one. In all of the other scenarios, notice, you still have all, or part, of your body left and involved. You are being gaslighted about the world around you and yourself, but you, and your body (which may be the same thing, in any case) are still in that world.

If you are entirely replaced by computer code, if you become part of a program, an abstract computational process, if you are part of a simulation, that’s very different than putting on a VR-rig or even being a brain in a vat. For one thing, if you exist only inside a program, I’m not sure what your metaphysical status outside of the program is – especially, whenever the program is not actively being run.